Promoting local pharmaceutical production has become a prominent policy priority across the globe, including in the United States, the European Union, India, and Africa. The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified long-standing concerns about reliance on imported medicines and vaccines, prompting support for initiatives aimed at localising production – defined as manufacturing within a geographical region, whether domestically or foreign ownership.

Calls for greater pharmaceutical production in low- and middle-income countries have been made for years (WHO, 2008). In a 2019 joint statement, UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), together with other United Nations agencies and the Global Fund, affirmed:

“In recognition of the important role local production can play in improving access to quality-assured medical products and achieving universal health coverage, the undersigned organisations aim to work in a collaborative, strategic and holistic manner in partnership with governments and other relevant stakeholders to strengthen local production”.

The African Context

Local pharmaceutical production has become a pressing priority for stakeholders in Africa.

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is one of the most populated regions in the world, with a stable population growth rate of over 2.5% for the past decade. This growth is accompanied by increasing healthcare needs. Alongside major communicable diseases such as lower respiratory tract infections, HIV/AIDS and diarrhoeal diseases, the continent faces rising rates of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which are projected to increase sharply over the next ten years. By 2030, deaths from NCDs in Africa are expected to surpass those from communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions combined. The demand for medicines is therefore particularly acute.

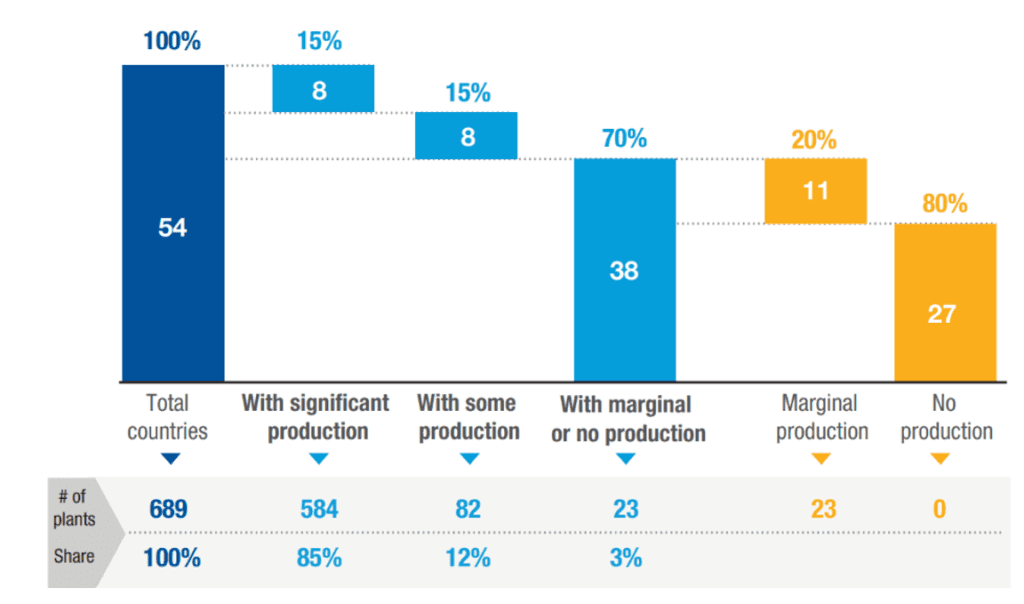

Despite this, Africa’s pharmaceutical market is heavily import-dependent, with more than 70% of medicines sourced externally, largely from Asia. Local production exists in about half of African countries (27 in total), yet remains minimal in over a third of them – 11 countries host fewer than five manufacturing plants (Figure 1). Overall, around 70% of African countries have little or no local pharmaceutical production. Of the remaining 16, half have moderate production (5 to 30 plants), while the others possess a more developed industrial base (more than 30 plants). Strikingly, this latter group of eight countries – half of which are in North Africa – accounts for 85% of Africa’s approximately 690 pharmaceutical plants, revealing a highly concentrated industry.

Figure 1: Around 70% of African countries have little or no local production footprint in pharmaceuticals

Source: UNCTAD Secretariat elaboration based on Banda et al. (2022).

Note: “With significant production”: above 30 plants; “With some production”: between 5 and 30 plants; “Marginal production”: below 5 plants. In the absence of systematic data on African production facilities, this mapping (from Banda et al., 2022) uses information from company websites, industry contacts, and networks. While precise numbers may vary due to uncertainties, the relative scales of production across countries (e.g., whether a country has significant, some, or marginal production) are reliable for analytical purposes. Due to lack of data, 11 countries – mostly small – were not mapped in the original analysis. For simplicity and completeness, they are included here under the assumption that they have no production facilities, based on empirical evidence from similar countries. Excluding them would not alter the underlying findings of the analysis.

Great disparities in access to healthcare and health infrastructure between countries are observed. North African countries and South Africa dominate the continent’s health services and drug production. South Africa is Africa’s first and largest drug producer, followed by Morocco, with Egypt and Tunisia also made progress in local pharmaceutical production. In SSA, aside from South Africa, only Kenya and Nigeria host a relatively sizable pharmaceutical industry, with several firms serving local markets and, in some cases, exporting to neighbouring countries.

Foreign Local Investments

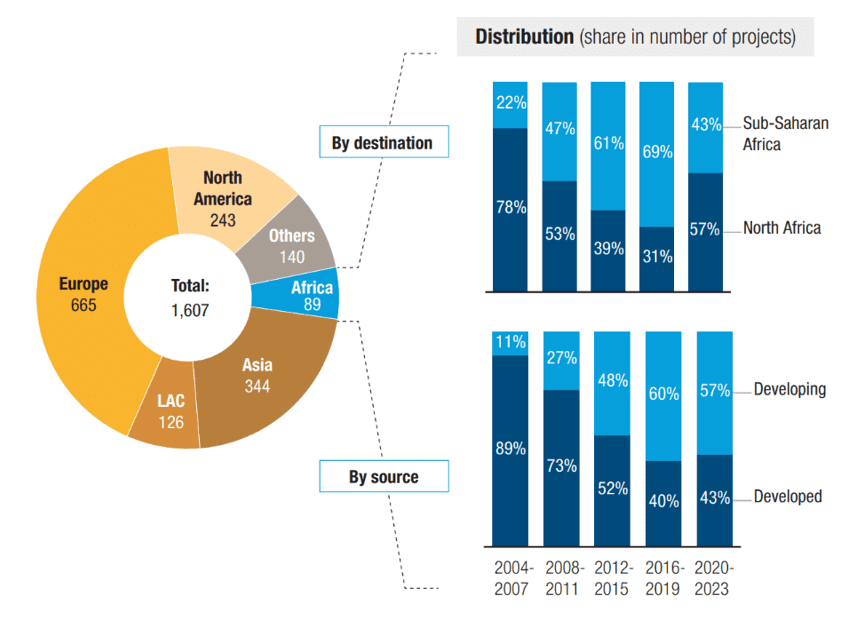

Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in Africa’s pharmaceutical sector has been limited. Over the past two decades, only around 200 cross-border greenfield projects were announced, fewer than 90 of which involved actual manufacturing (the rest focusing on sales, marketing and distribution) (Figure 2). By comparison, in the same period, Asia saw 350 such projects and Latin America and the Caribbean 130. Consequently, Africa’s share of global cross-border greenfield investment in pharmaceutical manufacturing remains low, at around 5%.

In recent years, the sources of investment have shifted: developing countries, particularly India, now account for the majority of projects, reversing the earlier dominance of investors from developed economies.

Figure 2: The FDI footprint in African pharmaceutical production is small (Number of announced cross-border greenfield projects in pharmaceutical manufacturing, 2004-2023)

Source: UNCTAD Secretariat, based on information from the Financial Times Ltd, fDi Markets (www.fDimarkets.com)

Note: LAC: Latin America and Caribbean.

Other Barriers to Access

Heavy reliance on imports raises drug prices and exposes populations to supply chain disruptions. In many Western countries, affordability is supported by social protection systems. However, most SSA nations lack such systems and cannot absorb the costs. For instance, in 2016 only 13.3% of Mauritania’s populations and 3% of Burkina Faso’s population were covered by public health insurance.

Weak procurement practices, inefficient public supply chains, inadequate transport networks and poor storage facilities further exacerbate the availability and affordability of medicines.

Africa also faces a critical shortage of healthcare professionals. Although the continent bears around a quarter of the world’s disease burden, only 3% of global healthcare workers are based there – with considerable variation between countries. This shortage limits access to essential medicines, particularly those requiring professional administration (e.g. intravenous monoclonal antibodies or chemotherapy).

A Disparity Between Global Drug Production and African Needs

Pharmaceutical innovation continues to prioritise Western markets. According to OXFAM France, only three new innovative molecules targeting diseases prevalent tropical countries were introduced between 1999 and 2004.

Given Africa’s vast genetic diversity, there is an urgent need for clinical trials involving the populations who most need these medicines. At present, most drugs are tested on predominantly Caucasian trial participants. This results in a lack of reliable data for Black, Asian and mixed ethnic populations, raising concerns about the applicability of findings. It hampers the ability of researchers to manage disparities and undermines efforts to design targeted policies and community interventions to achieve health equity.

The evidence points to a pressing need for innovative approaches to address Africa-specific health challenges.

Conclusion

Access to medicines in SSA relies on the coordinated actions of multiple stakeholders: policymakers, government agencies, private companies, healthcare professionals and civil society organisations.

Developing the continent’s pharmaceutical industry could yield significant benefits across three dimensions:

Health: Expanding local production would improve access to essential medicines such as antibiotics, reduce inequalities, and generate substantial public health gains.

Strategic: Localising pharmaceutical production would reduce dependence on imports and strengthen supply security during crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. While active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) production remains concentrated in China and India, building local formulation capacity represents a crucial step towards self-sufficiency.

Economic: Industrial localisation could create skilled jobs, advance knowledge-intensive industries, and stimulate broader economic growth, even if value added at the formulation stage is relatively limited.

Veronique Ropion, MD

Director of Business Strategy, Marketing & Corporate Communication

Sources:

- Diane Deville. Access to Medicines in Sub-Saharan Africa – How to build a path for sustainable business models? Alcimed April 2023:1-24.

- United Nations. Policy review – Building the case for investment in local pharmaceutical production in Africa. A comprehensive framework for investment policymakers. United Nations 2025:1-83.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Attracting pharmaceutical manufacturing to Africa’s special economic zones. United Nations 2025:1-37.